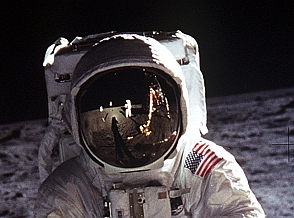

It’s not every day that you get to sit in front of someone who has walked on the surface of the Moon. Today I was given just such an opportunity, a conversation with Buzz Aldrin which took place at the newly refurbished House of St Barnabas – which for the Olympics madness has been knighted as Omega House, a private hospitality venue in the centre of London named after the illustrious watch-making company and official timekeepers of the London 2012 Olympics.

It’s not every day that you get to sit in front of someone who has walked on the surface of the Moon. Today I was given just such an opportunity, a conversation with Buzz Aldrin which took place at the newly refurbished House of St Barnabas – which for the Olympics madness has been knighted as Omega House, a private hospitality venue in the centre of London named after the illustrious watch-making company and official timekeepers of the London 2012 Olympics.

The venue could barely withstand the level of interest in seeing such a legendary figure speak, and the mixed group of media and guests were separated into two rooms. First to listen to a presentation by Buzz Aldrin on his experiences with the Apollo Programme and then a multi-room Q&A that covered everything from the need for a renewed focus on Mars (a manned mission which he predicts will occur by 2040) to a question one would guess came from an Omega spokesperson as to why Buzz chose to wear one of their watches when he first stepped onto the lunar surface. For the record, Buzz gave a masterful stroke of non-marketing by saying that there was ‘nothing more useless when you’re on the surface of the Moon then knowing the time in Houston, Texas.‘ You’ve got to respect an answer like that.

Beyond the truly inspiring rhetoric, and the desire to see renewed focus on the exploration of space and its eventual colonisation, there were interesting undertones of patriotism that displayed Buzz Aldrin’s well-known Republican leanings. It sounded slightly anachronistic when we consider projects such as the Large Hadron Collider and the collective efforts that brought it such success to hear this impressive man speak of national competitiveness. Not to mention a kind of dissonance when he says quite passionately that ‘we as a Nation need to…‘ – clearly the people he was addressing, given our location and international context, were not the ‘Nation’ he was talking of. To be fair, he did close one of the final questions by saying that we ‘need to be competitive on the small things, and work together on the big.‘ To be even more fair, he walked on the frickin’ MOON.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t one of those selected to put forward a question so I thought it would be worth asking here and exploring some of the reasons why I would have been interested to hear his answer. Quite simply, I wanted to ask: Do you think we should allow the privatisation of space? In a session that was filled with both talk of national accomplishments and inspiring collective human endeavours, there was little mention of the commercialisation of space exploration and the consequences of allowing a privatisation of this new frontier. When we consider the recent SpaceX mission, which was the first commercial company to dock with the International Space Station, it’s becoming increasingly likely that any successful mission to Mars – particularly one that has a persistent presence – could well be a privately funded enterprise.

With the NASA Curiosity rover scheduled to touch down in just three days, it brings up interesting questions about the relationship between publicly and privately funded space research and the motivations driving missions in the future. Is it a case where the bulk of the research and development will be publicly funded, and then those with deep pockets are best positioned to use this research for sustainable programmes that have profit margins in mind?

With the NASA Curiosity rover scheduled to touch down in just three days, it brings up interesting questions about the relationship between publicly and privately funded space research and the motivations driving missions in the future. Is it a case where the bulk of the research and development will be publicly funded, and then those with deep pockets are best positioned to use this research for sustainable programmes that have profit margins in mind?

NASA’s commercial crew programme is set to pump over half a billion dollars worth of state spending into developing privately operated enterprises – with the justification being that it will reduce future budgetary demands. The socialisation of cost and the privatisation of profit is a theme that seems to be occurring frequently in our ‘free market’ society recently, and it is one that in the US at least looks to be replicated in the space sector.

In the short term, it might seem that this commercialised approach is not only inevitable (given the rights of companies and individuals to produce technology capable of such feats) but also desirable. There are many advantages that private spaceflight can bring to the table, and a competitive market will drive down production costs, increase research and development capabilities, and probably mean that we achieve milestones much quicker than if we were to wait for underfunded government programmes (particularly at a time of global recession).

In the longer view, some pivotal questions are raised which need to be openly tackled. Who can claim ownership of land or resources on other planets or moons? Will the private market create an access problem in which only the richest members of our global society are able to participate? Will the sense of cosmic wonder and collective ingenuity be replaced with a corporate battleground of patents, lawsuits and profit margins? Perhaps the most important question…is it just going to be first come (or go as the case may be), first served?

How we treat the extension of humanity beyond planet Earth will dictate the very philosophical foundations that we build our future social identity around. Yes, it might be true in the current socio-economic context that many of the things we dream of cannot be achieved without privatisation of one kind or another – but at what cost, then, will our dreams be fulfilled?

How we treat the extension of humanity beyond planet Earth will dictate the very philosophical foundations that we build our future social identity around. Yes, it might be true in the current socio-economic context that many of the things we dream of cannot be achieved without privatisation of one kind or another – but at what cost, then, will our dreams be fulfilled?

If we privatise the exploration and colonisation of our solar system can we truly say it was done out of a sense of uplifting and evolving humanity towards a more unified, collective vision of what it means to create and exist? Or will our vision be determined by those who had the means to get their first, solidifying further their place at the top of the global hierarchy.

Many of these questions are covered by various articles of the Outer Space Treaty – currently ratified by 100 countries, with more to come. This treaty provides a promising basis for our future explorations, including the concept that bodies such as the Moon or planets such as Mars should be considered the ‘common heritage of mankind’ and therefore protected from some of the worst case scenarios we might imagine. Such a treaty is a good foundation to start from, but we’re already seeing that there is quite a bit of leeway in how it can be interpreted.

Consider plans to create for-profit asteroid mining companies, lauding their ability to ‘add trillions of dollars to the global GDP’ (or the balance sheet of the corporations who achieve such feats). A cursory reading of the Outer Space Treaty would lead you to believe that such an enterprise would fall under ‘appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means’. But apparently this is not the case…Treaties are only as good as the level to which they are enforced and the degree to which they are unambiguous. Also, the OST is designed to specifically deal with matters of national sovereignty and doesn’t really concern itself with private business matters. There’s a clause on page 40 which states that ‘the activities of non-government entities in outer space shall require authorization and continuing supervision by the State concerned‘. Ambiguous, at best.

Which is not to mention the fact that the Outer Space Treaty does not deal with important links in the chain of interstellar exploration. NASA is seeing itself move towards a model where commercial space flights are key – whilst countries such as Russia and China are keeping their programmes tightly under state control. Whether or not a single national or corporate body can claim sovereignty over particular areas of space is less relevant then their ability to monopolise the means of access. Sovereignty is less of an issue when you’re the only one capable of extracting those minerals from asteroids, and you control the patents and means for others to do the same.

It’s kind of a difficult concept how one can sell interstellar resources for private profit when they are considered to be the ‘common heritage of mankind’. When they get back to Earth will the payloads of these missions be distributed evenly amongst all parties who wish to profit from them? If that were to be the case, who would bear the brunt of the financial risk and costs – and must they be compensated with significant rates of return? If we don’t allow sovereignty and we feel that privatisation is undesirable does that mean that we need to forego space exploration altogether?

In order to achieve some of the outcomes that many are hoping to see in their lifetimes it is inevitable that we will see an increasing move towards privatised models of space exploration and commercialisation. The ‘Space Rush’ period will see the demise of many well-funded companies as the risks for involvement are so high, but the possible rewards are also astronomical in value (sorry…couldn’t let that one pass). It strikes me that we need to consider our approach to this transitional period of human history far more carefully then we are currently doing, particularly in the sense of our general public engagement with the questions at hand. By relying on national interests and government processes we also rely on traditional lobbying streams, and it’s quite clear who will win out if those forces are left to their own devices.

Our exploration of the solar system and beyond should be seen as the best chance we have at overcoming our biological nature for territorialism, hostility and competition; replacing it instead with a mode of action that builds upon our capacity for empathy, compassion and collective wellbeing. Commercial enterprise will definitely play an important role in getting us to the point where we can spread our wings as a species and expand into a new destiny. We just need to ask ourselves what that destiny might look like, who will form it, and who will be the primary beneficiaries.

Our exploration of the solar system and beyond should be seen as the best chance we have at overcoming our biological nature for territorialism, hostility and competition; replacing it instead with a mode of action that builds upon our capacity for empathy, compassion and collective wellbeing. Commercial enterprise will definitely play an important role in getting us to the point where we can spread our wings as a species and expand into a new destiny. We just need to ask ourselves what that destiny might look like, who will form it, and who will be the primary beneficiaries.

Heading off to the stars is not merely a matter of spectacle to be read or watched from a distance, it is quite literally a new dawning for humanity. Is that really something we’d be willing to sell to the highest bidder?

I realise I’ve thrown a lot of questions out there with this post, a lot of what ifs and how abouts without too many answers following. This is partly because it’s an area that I haven’t done much detailed research into, and I’m using this post as a springboard into the topic. I’d very much like to hear your thoughts on these questions, so please do leave a comment below.