The contagion of mistrust was always going to spread further, but it was an open book as to where it was going to emerge next. Corrupt and deeply embedded behaviours found in the financial, media and political spheres over recent years have left much of the general public completely disillusioned with those who have been deemed ‘Masters of the Universe’ – keepers of the social narratives that rule our lives, dictate policymaking and direct economies around the globe.

The contagion of mistrust was always going to spread further, but it was an open book as to where it was going to emerge next. Corrupt and deeply embedded behaviours found in the financial, media and political spheres over recent years have left much of the general public completely disillusioned with those who have been deemed ‘Masters of the Universe’ – keepers of the social narratives that rule our lives, dictate policymaking and direct economies around the globe.

Perhaps nobody was really surprised by the recent exposure of emissions testing fraud coming from Volkswagen, but the brazen and conscious deception enacted in the pursuit of corporate profit was, in the words of one commentator, ‘striking in its apparent villainy’.

Beyond this recent scandal of 11 million fraudulent vehicles, the list of corporate deception and exploitation of people and planet is shockingly comprehensive. By now we are well acquainted with the generational destruction wrought by global finance (with less well-known examples such as the profiteering of Goldman Sachs in Greece); but add to that systematic hacking by the media; unethical psychological experimentation through social media; demolishing investor value by overstating profits; directly lobbying against environmental policy protections; profiting from slave labour in the supply chain; massive levels of corruption in the world of sport; the list really could go on, and on, and on, and on…

There are clearly very good reasons as to why the general public might be losing trust in both the corporate sector and our political representatives who are so beholden to it (the recent surge in popularity of both Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn’s message of honest politics is a result of this), and so the question that many have begun to ask is: just how do we restore that trust?

A great deal of time and energy has been put into well-constructed regulatory efforts, particularly in the financial sector, and many of these do seem to go far enough to stop to a lot of the potential for misconduct (which, in other areas of life, would be called crime) that we have seen over recent years. Just as much energy, and even more rhetoric, has been put into the equally important but far more evasive areas of self-regulation that fall under the umbrella of ‘culture’. It’s hoped that a strong combination of these two things will restore the virtue of the private sector, so that it might once again be a paragon of social infrastructure attached to a clear notion of civic duty.

The problem is, though, that even if these efforts prove successful it’s likely that they won’t be enough to restore trust. For one simple reason: you can’t restore trust without addressing power.

Power is the elephant in the room that many people are trying to avoid noticing. Focusing on the technicalities of corporate functioning and the professional conduct of people in business, although certainly necessary, is in many ways overlooking the true root of the collapse in public trust. The problems that we have seen have been a result of combining ever-more powerful institutions with a market-driven ideology that crowded out the ability for regulatory fail-safes through a ‘cognitive capture’ of government policy and access that placed the collective voice of the private sector above almost every other element of society.

Furthermore, this accumulation of power leaned towards a very small number of entities (80% of global corporate control is held by only 0.61% of shareholders, predominately financial institutions, whom behave as a single economic ‘super entity’). This has created massive problems with market competition and systemic risk, has placed companies that are supposed to be intermediaries as expensive, publicly subsidised profit takers, and has greatly skewed the policymaking of governments around the globe – often to the detriment of social services and initiatives promoting public wellbeing.

Those with power and authority must prove their legitimacy and be held to incredibly high standards of social purpose, obligation and positive effect. Many of the current corporate structures have done exactly the opposite in a very clear manner, which is why their authority is being questioned and many are looking for ways to remove them from entrenched positions of power. This is really what the loss of trust ultimately demands and why many people are so concerned about restoring it, being intrinsically connected to the accumulation of power and the promotion of one vested interest (private wealth) over another (public wellbeing). You cannot restore such legitimacy in the eyes of the general populace unless this tension is openly discussed and substantial concessions genuinely offered.

Developing a notion of flourishing societal diversity, and how the narrative primacy of finance capitalism is working against such a view, is vital for steering us clear of the insatiable desire for power (manifest primarily through networks of ownership) that the market economy has provided to those who have placed themselves as custodians of its operative mechanisms. This is not ‘banker bashing’ or ‘wealth envy’ but simply to ask that the private sector justify many aspects of its activity that often come at a great expense to the rest of society, and to recognise that its needs are not the only important component of a healthy economy nor society as a whole.

An important aspect of restoring trust is thus to openly challenge the fundamental assumptions that the private sector has relied upon, particularly over the past half century. These are found in the form of economic and political assumptions (as Adair Turner famously put it: “a sort of 50 year-long giant intellectual mistake”), but they are also relational and boil down to assumptions about the extent to which each individual has a duty to serve the interests of their community and humanity (not to mention the diversity of life on this planet). Such reciprocal relationships form the bedrock of our social structures and hierarchies, and they have been torn apart by the dominance of power-driven ideologies that benefit from breaking the bonds between members of society. Encouraging the accumulation of private wealth over promoting a mature level of compassion for and solidarity with the lives of others we may not personally know.

An important aspect of restoring trust is thus to openly challenge the fundamental assumptions that the private sector has relied upon, particularly over the past half century. These are found in the form of economic and political assumptions (as Adair Turner famously put it: “a sort of 50 year-long giant intellectual mistake”), but they are also relational and boil down to assumptions about the extent to which each individual has a duty to serve the interests of their community and humanity (not to mention the diversity of life on this planet). Such reciprocal relationships form the bedrock of our social structures and hierarchies, and they have been torn apart by the dominance of power-driven ideologies that benefit from breaking the bonds between members of society. Encouraging the accumulation of private wealth over promoting a mature level of compassion for and solidarity with the lives of others we may not personally know.

These assumptions have taken root in the corporate world – they are not inherently of it, but can thrive within its numbers-based abstractions – and we need to challenge their existence. It’s not enough to respond with slightly repackaged promises of shared prosperity and the irreplaceable nature of access to goods and services, a truly reconciliatory response would begin to explore the areas in which such activities should start to withdraw from the formation of society and would actively begin to encourage innovative alternatives instead. We need a healthy, functioning private sector for many important things – but we also need to forthrightly acknowledge that the accumulation of power has become counter-productive to our shared wellbeing and human flourishing, and that the fall-back position of acting for shareholder value alone is a corrosive way to operate an economy.

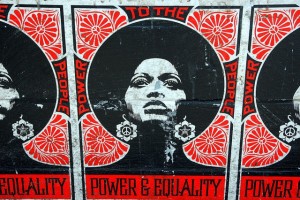

This whole discussion is wrapped up in the urgent context of global inequality. This was the inherent message expressed globally through the Occupy protests four years ago, which sharply questioned whether a system that consisted of endemic inequality should be heralded as a positive vision of the way society should function. These protests, and many others like them, were essentially arguing that there is an imbalanced and unfair relationship at the core of contemporary capitalism, which seeks to commodify and instrumentalise for profit as many aspects of our lives as possible. Secondarily, and importantly here, that financial sector institutions in particular were the ones gaining the most out of this imbalance whilst returning relatively little social value from new avenues of product ‘innovation’. A large part of this critique also relied on the excessive interconnectedness between money and politics, with the decision-making which results from such self-serving connections effectively shutting out the needs and voices of large swathes of humanity.

Restoring trust is a two-way street, and so it’s vitally important to develop an understanding that social progress is an ongoing process requiring an interdisciplinary and multi-faceted approach – one with no fixed or definable goal beyond the integrity of the transformative process itself. Anything else is to place a limited perspective that will be heavily biased by historical and ideological forces and primarily serve one subset of people over others.

This process should be reflexive and self-aware, have multiple points of intervention and avenues for change, promote self-expression within a context of mutual benefit, and should not be beholden to vested interests and hidden channels of influence. The goals will change in response to circumstance and need, with more focus on specific and precise actions, and from this the mechanisms we use to achieve them will emerge accordingly. As Pope Francis laid out in the recent encyclical Laudato si’: “we are always more effective when we generate processes rather than holding on to positions of power.”

The importance of seeing the future as a process that unfolds in this way is that it encourages wide-ranging and inclusive conversations to take place that inform the public discourse, and this inclusive dialogue then directs the efforts of technical experts to formulate innovative responses. In the world today we have gotten this relationship backwards, as those with deep specialisation feel entitled to solve problems often of their own creation without wider consultation with those most affected.

The importance of seeing the future as a process that unfolds in this way is that it encourages wide-ranging and inclusive conversations to take place that inform the public discourse, and this inclusive dialogue then directs the efforts of technical experts to formulate innovative responses. In the world today we have gotten this relationship backwards, as those with deep specialisation feel entitled to solve problems often of their own creation without wider consultation with those most affected.

In the context of the private sector, this has approached fantastical levels of hubris – where it is still presumed to be the most productive and inclusive way to achieve the advancement of modern global society as a whole, even though we have seen multiple examples within a single generation that provide us with clear evidence that this just isn’t currently the case.

In the end, you can’t restore trust unless there is potential for restructuring the hierarchy of relationships and systems of power that enabled a betrayal to occur in the first place. If we’re not willing to talk seriously about more widespread and lasting systemic change that impacts the primacy of the private sector – above and beyond iterative developments around trading rules, product codes and market structures – then ultimately nothing is being done to address the systemic imbalances causing disenfranchisement, frustration and poverty for a large, growing number of people in modern society.

Where this difficult conversation is taking place it is clear that it isn’t yet being taken seriously – as those who are currently benefiting the most don’t really want anything to change at all. Yet the message is becoming increasingly unavoidable. If the overseers of the profit-driven status quo don’t begin to embody a more holistic view of what it means to create an inclusive social order, then society will eventually be forced to move forward without them…having waited long enough for promises of change that never truly come.