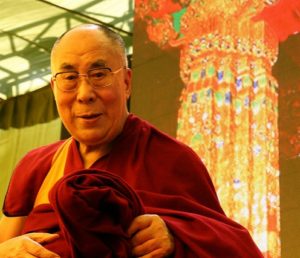

Image above by Bill Smith (CC, Flickr)

It is increasingly common to say that the next World War will begin over the internet. As modern economies and the infrastructures we rely upon become ever-more connected, our ability to protect ourselves from malicious attack hasn’t been able to keep up the same pace. This is a concern for individuals, as well as private sector businesses seeing an almost unstoppable barrage of attacks, but it is also vitally important for geopolitical security and the ability for state-sponsored attacks to cause massive – potentially catastrophic – disruption on an international level.

Government-to-government cyber espionage, attacks, hacks and warfare (pick your term according to context and/or scale) have been drawn back into the spotlight recently with the assertion that the recent leaks from the US Democratic National Committee, as well as the newly acknowledged hacks of the Clinton campaign, are the result of hacks sponsored by the Russian government. Whether or not this narrative is ultimately true, and it will be interesting to see what further evidence might be supplied of such, the notion that governments would subversively undermine one another is certainly a fact and occurs far more often than can be ascertained through publicly available information.

Although we will never really know the full extent of such tactics and intrusions, there are some key moments that we can look to in order to understand the techniques used and targets attacked. With the rhetoric ramping up considerably against Russia, we seem to be reaching a new level of public involvement in debate around state-sponsored cyberwarfare. Here are a few important examples over recent years that to some extent show us the scope of the issue.

Stuxnet (2010, USA/Israel -> Iran)

One of the most sophisticated acts of cyberwarfare currently known has been attributed to an attack by the United States and Israeli governments on Iran’s nuclear capabilities through the use of a highly technical and cutting-edge software virus. Various different versions of this worm, including one spread via USB flash drives, self-propagated over Microsoft Windows systems until it was loaded onto certain types of industrial platforms. About 60% of infected systems were reported to be located within Iran, making it a clear target of the attack, and in 2012 reports confirmed that the virus sabotaged centrifuge systems used in the enrichment of uranium but had gotten out of control and became impossible to contain as it infected computers all over the globe. This attack was followed up with another piece of malware called Flame which conducted surveillance on networks throughout the Middle East, particularly again in Iran.

Operation Cleaver (2014, Iran -> Many)

Perhaps as part of retaliation to the Stuxnet/Flame attacks, in 2014 it was reported by the cybersecurity company Cylance that hackers with ties to the Iranian government had operated co-ordinated attacks against more than 50 targets in 16 different countries. Through a wide-variety of different tools and methodologies, the report outlined a large net of different targets including energy companies, defence contractors, airports and airlines, transportation networks, telecommunications companies and universities. The results of these attacks ranged from data theft (including passport and social security information) and corporate espionage, through to ‘complete access’ attacks that could control airport security systems.

Perhaps as part of retaliation to the Stuxnet/Flame attacks, in 2014 it was reported by the cybersecurity company Cylance that hackers with ties to the Iranian government had operated co-ordinated attacks against more than 50 targets in 16 different countries. Through a wide-variety of different tools and methodologies, the report outlined a large net of different targets including energy companies, defence contractors, airports and airlines, transportation networks, telecommunications companies and universities. The results of these attacks ranged from data theft (including passport and social security information) and corporate espionage, through to ‘complete access’ attacks that could control airport security systems.

An Iranian spokesperson denounced the report at the time as ‘baseless and unfounded’ and there was debate about its approach and validity. However, it is known that Iran took a keen interest in the area – as seen by the establishment of its Supreme Council of Cyberspace in 2012 and (perhaps independent) active hacking groups with a long list of high-level activity.

Operation Orchard (2007, Israel -> Syria)

In 2007 it was reported that the Israeli air force had conducted a mission against an in-progress nuclear reactor target in northern Syria, just south of the Turkish border. One of the interesting aspects about this highly-secretive attack was that the fighter jets were able to travel hundreds of miles through enemy territory, all without receiving any retaliation from the Syrian air-defence network. Israeli aircraft had successfully employed electronic equipment that blinded the Syrian defences. Whilst this attack doesn’t contain the kinds of cyberpunk hacker groups or covert spy networks that mark the other examples included here, it does show that there are often close connections between state-sponsored cyberwarfare and traditional military attacks. It was suggested at the time that the attack could have utilised the Suter software developed by BAE Systems that hacks into systems rather than jams them. Others suggest that it may have been enabled by off-the-shelf microprocessors that had been installed with a hidden backdoor – highlighting the difficulties with securing networks that are reliant upon global trade for their construction.

GhostNet (2009, China -> Many)

The discovery of malware on computer networks used by the Dalai Lama led to an investigation that named a loosely co-ordinated effort to attack and infiltrate systems in 103 countries. The markers of this vast espionage network, named GhostNet by the investigators, suggest it was conducted under the supervision of the Chinese government; although others state that it could just as likely be a case of widespread cybercrime rather than cyberwar.

The discovery of malware on computer networks used by the Dalai Lama led to an investigation that named a loosely co-ordinated effort to attack and infiltrate systems in 103 countries. The markers of this vast espionage network, named GhostNet by the investigators, suggest it was conducted under the supervision of the Chinese government; although others state that it could just as likely be a case of widespread cybercrime rather than cyberwar.

However, when taking a longer view the evidence certainly stacks up with common sense that the world’s major superpowers are engaged in almost continuous cyberwarfare. GhostNet is an important moment in state-sponsored cyberwar because it shows the extent of politically-motivated infiltration throughout global computer networks (in the case of China traced back to the ‘Titan Rain’ revelations of 2003). This has reached the point that major companies such as Microsoft have stated in the past that they will directly notify users they believe have been the target of state-sponsored hackers (does this include the CIA or NSA?), although there also seems to be recent progress made between the USA and China in stepping back on hacking activities between the two nations.

The Russo-Georgian War (2008, Russia -> Georgia)

The Russian invasion of Georgia in 2008 was a short but violent conflict the repercussions of which are still unfolding. During the lead up to the military conflict there were a large number of cyberattacks on Georgia that took down websites and servers, redirected and blocked internet traffic, defaced government and targeted news agencies. These attacks seemed to link the world of underground cybercrime in Russia – including the notorious Russian Business Network – with military operations. Difficult to ultimately place at the feet of the Russian government, at least one hacker supposedly involved stated that these activities were more to do with patriotism than directly state-sponsored. This ‘combined kinetic and cyber operation’ was seen again during the 2014 annexation of Crimea; however, showing that the line between physical and cyber attack has become increasingly blurred in modern conflict. These complex relationships between individuals, underground groups, and state agencies make it difficult to place accountability on governments even when there is clear indication of high-level co-ordination.

War on Terror (2001-present, USA -> Many)

For the past 15 years we have lived in the era of the ‘War on Terror’ and currently escalating tensions make it likely that this mode of existence won’t be going away within the next generation, at least. Cyberwarfare has played a key role in this war with a seemingly limitless number of enemies, even to the extent of massive erosion of civil liberties and the expansion of domestic surveillance programmes on innocent citizens throughout supposedly democratic countries around the world. State-sponsored cyberattacks have been conducted against numerous extremist groups, particularly those linked to al-Qaeda and now ISIS. When she was still Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton openly talked about these efforts and these public statements of cyberwar strategies have continued from senior US military officials since. Indeed, it is interesting to consider that these tactics are now openly admitted and discussed.

For the past 15 years we have lived in the era of the ‘War on Terror’ and currently escalating tensions make it likely that this mode of existence won’t be going away within the next generation, at least. Cyberwarfare has played a key role in this war with a seemingly limitless number of enemies, even to the extent of massive erosion of civil liberties and the expansion of domestic surveillance programmes on innocent citizens throughout supposedly democratic countries around the world. State-sponsored cyberattacks have been conducted against numerous extremist groups, particularly those linked to al-Qaeda and now ISIS. When she was still Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton openly talked about these efforts and these public statements of cyberwar strategies have continued from senior US military officials since. Indeed, it is interesting to consider that these tactics are now openly admitted and discussed.

There are also some parallels here with the Russian-linked cyberattacks described above, in that many patriotic lone actors have begun to join alongside official US operations. These range from satire-laden attacks from various groups/people identifying as Anonymous through to targeted hacktivism from individual hackers such as ‘The Jester’. This new front of global cyberwarfare isn’t one-sided, though, as there are also attacks that ISIS have claimed responsibility for. What we are seeing with the ‘War on Terror’ is that the boundaries of warfare are rapidly shifting and the digital realm is a key battleground that will only continue to grow in importance and consequence.

Conclusion

Protection from digital threats is a vital component of a healthy society in the modern world, but when offensive campaigns are conducted without proper public oversight and little to no accountability for the unintended consequences (or collateral damage) of such actions there is a need for citizens to become better informed and more assertive in our questioning of actions taken for our supposed benefit. The list included above is nowhere near comprehensive (with more space I would have definitely included the Sony Pictures Entertainment hack attributed to North Korea), nor could I give as much detail as each of these individual cases deserves. The articles and reports linked throughout this article will give you a far greater insight and a glimpse into the new global reality of extensive state-sponsored cyberwarfare that we currently live within.

Although there has been significant resistance to physical war and the devastation that it causes, there has been relatively little activism directed at the reality of cyberwarfare and the ethical questions that arise from its conduct. As proactive and responsible citizens, we need to be holding these programmes to account. It’s an almost impossible task, given the secrecy and deniability that surrounds such programmes, but as an increasingly open aspect of geopolitical tensions in the 21st century we can’t afford to ignore the impact that such attacks are having on the relationships between nation-states.

Like most political decisions that happen on the global stage, there is little integration with the wants and needs of everyday citizens into the machinations of institutional power. Decisions are made for us, but rarely with us. It’s time to engage with the realities of cyberwarfare, protecting ourselves as individuals and communities as much as possible whilst bringing the broader ethical issues further out into the realm of public accountability.